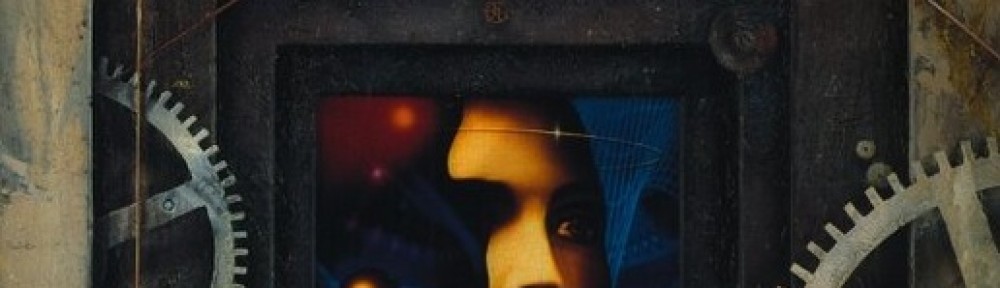

Reality

Scene 33

The ReHumanist Manifesto. October, 1975. For Private Circulation Only.

Page 34

The Mechanism

Men have not always needed to know how a thing worked for them to use it to their advantage. Henry’s archers at Agincourt devastated the French nobility without any knowledge of the “Law” of Gravity or the equations Newton produced 260 years later, though their arrows’ paths were precisely “determined” by those laws, in a manner of speaking. Electricity was supremely important and useful before the discovery of the electron, as was fire before the understanding of oxidation.

In the 1930s much of the world, and most especially some of my colleagues in the science fiction field, were intrigued by the research done at Duke University into “parapsychology,” led by Dr. Joseph Banks Rhine. Dr. Rhine claimed to have demonstrated “extrasensory perception” (ESP) through a long series of laboratory trials that found certain people who could seemingly “see” hidden cards through a kind of “mind power.” After a few years of extensive use of ESP in the science fiction pulps, it gradually became clear that Rhine’s results were not replicating in experiments by others, and interest began to fade, though the idea cropped up again with regularity—ESP might or might not work in our world, but did in this or that fictional world.

This is the point of fiction.

Among the so-called “general public” there was always, and continues to be, a majority belief in the “supernatural.” This muddy category might include the aforementioned ESP, ghosts, precognition, the Transubstantiation, spirit mediumship (something that Rhine got his start debunking), “UFOs” (in all their permutations), etc., etc., etc. The reader can lengthen the list as necessary for purposes of discussion.

What do all of these things have in common? First, “science” has supposedly “debunked” them, declared them impossible, or at the least failed to replicate them experimentally. “Science” long ago was defined as the study of the material world, of matter, that is, atoms and the Void. That’s why elsewhere in this Work I mock “social science” so mercilessly. At its best, social science is the gathering and analyzing of useful statistical correlates. At its worst, it is propaganda designed to get the masses to do what our Masters want.

And yet: The “power of positive thinking” was known long before Dr. Peale’s excellent book, was commented on by authors from Classical Greece to Victorian Britain. If there is only matter, then thinking is merely the firing of neurons and the allocation of electrochemical energy. So at first psychological “science” sought to debunk such notions as thoughts influencing the physical body—until the experimental results began to debunk the debunkers. Positive thoughts were shown, with merciless statistical precision, to increase the likelihood of long life and health, to predict success in work and at school, to assist in victory in athletic competition—in short, the power of positive thinking was scientific!

And of course, this challenge to materialism was met by conjuring up…more materialism! Because there must be a material mechanism to explain all results, all phenomena, all Reality. The reason this must be so is that science has deliberately excluded everything else. Positive thinking must be understood to change hormone levels, blood chemistry, the activity of the parts of the brain that react to stress, or something of this sort.

This was mere papering over of a tremendous void, of course.

Let us consider a man suffering from intense sadness (“depression”) because he’s stranded, alone, on an isolated island. We would all agree, superficially, that he has a right to be sad, given the circumstances. Now, let us say he is one day sitting on a rock upon his island, and he sees a tiny spot of something on the rock that is a different color than he’s seen around heretofore, a different and rarer type of lichen, perhaps, and he takes a deep breath and says to himself “I will not give up” and with this thought he begins to feel somewhat better, and the change reminds him that he can change, and he speaks to himself internally: “I Will feel better,” and he begins to do so.

Now one might try and posit a “mechanism” here, something like: “The light waves of a slightly different frequency than his brain had observed for some time were translated in the visual cortex to electrochemical information that propagated through various organs of the brain resulting in a series of chemical changes that he felt as ‘better.’ And this feeling caused another cascade of similar effects that caused a projection of this feeling into the future.”

I submit to you, Dear Reader, that this reads like a fairytale: “One day the boy found some Magic Beans in the garden…and he felt better.”

I will now give you a “scientific” proposition of my own to ponder: All our known sensory organs are made of atoms, and thus the only things they can sense are other atoms that bounce off of them or combine with them to form new chemicals, or electromagnetic radiation that alters their electrons. This is elementary physics and chemistry. If, if there were any other kinds of “substances” in the universe besides atoms and photons and so on, our senses would not be able to detect them, directly.

To be “scientific” in our time is to deny that there is a possibility that there are any of these other substances. This was always my position, from the time I began to think for myself, age 12 or so, the time I read of Eddington’s observational test of General Relativity during the 1919 eclipse. It was my position as I wrote and sold my science fiction stories of the 1930s—ESP was included because it had been shown to work in the laboratory. And when that came into serious doubt I abandoned it. It was my position through the 40s and early 50s, in my novels about space travel and future life on Earth.

And then it came to pass that events changed my mind, not in the theoretical sense of laboratory results, but in “real life.”

And I found there that besides matter and the void, there is indeed a third thing, and that we do have a way to contact it. Our ancient ancestors knew the way, I believe, and Man traded it, in effect abandoned it, for the material technology that allowed him to grow from tens of thousands to billions of individuals in just a few tens of thousands of years. In many ways it was a very good trade for him.

But now I understand that it isn’t gone forever. It can be gotten back.